The Newsroom / History of Paper / The Enslaved Woman Who Became a Poet

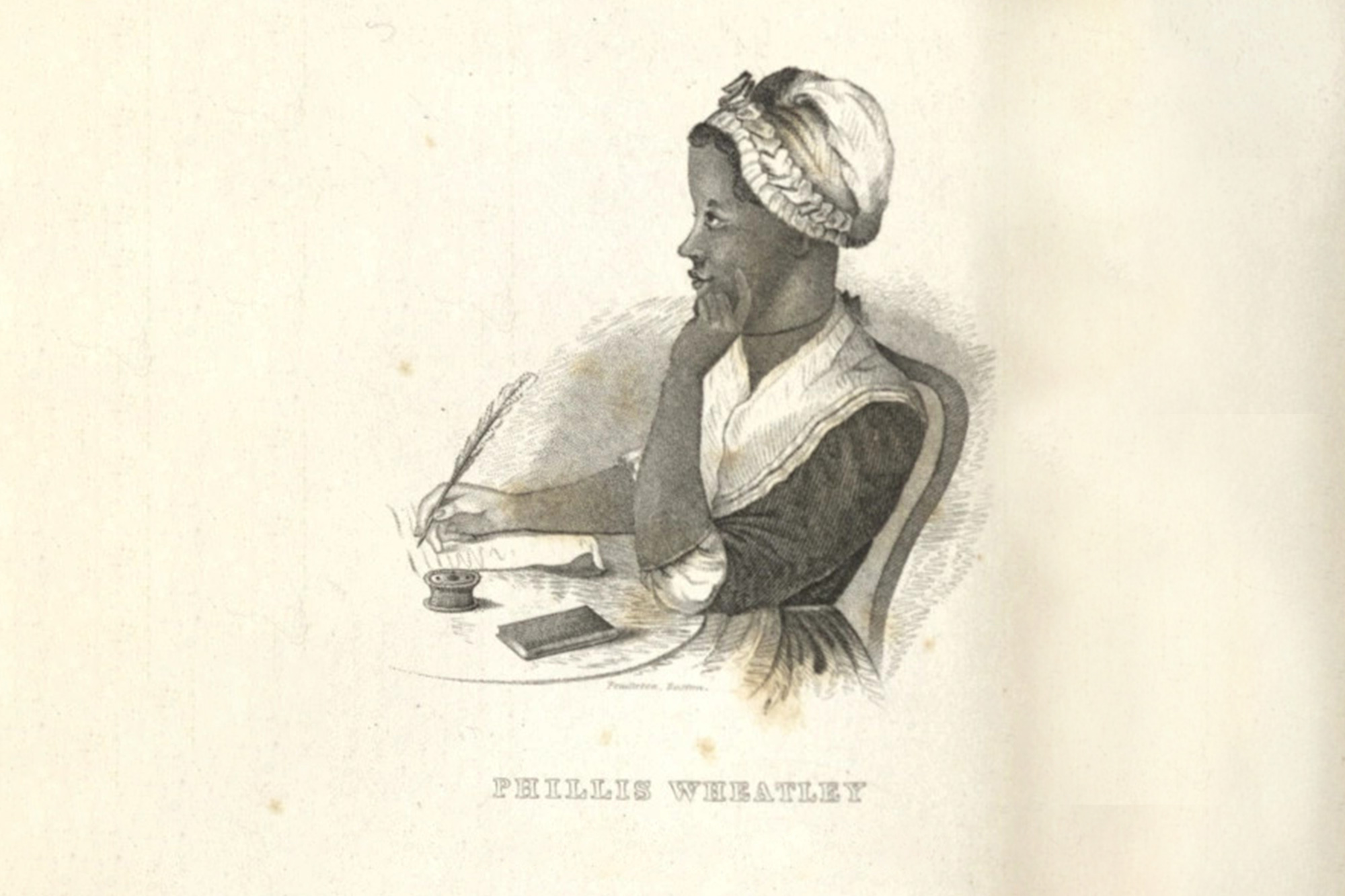

The Enslaved Woman Who Became a Poet

To mark Black History Month, Hammermill® is sharing the story of a woman who was well-known to the educated people of the Colonial era, and deservedly so.

More than 200 years ago, in 1773, a poet named Phillis Wheatley became the first African American woman to publish a book. Her book was titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. She was just 20 years old when it was published. But perhaps the most remarkable part of her story is this: Phillis was enslaved at the time.

Phillis Wheatley’s Early Success

Phillis Wheatley was born around 1753 in West Africa. She was kidnapped by slave traders at seven years old and brought to Boston on a ship called The Phillis (her namesake). There, she was sold to merchant John Wheatley as an enslaved servant for his wife, Susanna.

The Wheatley children, Mary and Nathaniel, taught Phillis to read and write. By the age of 12, she could read Greek and Latin classics, in addition to difficult passages from the Bible. Recognizing her talent for language, the Wheatley family encouraged Phillis to pursue the poetry she had begun to write.

In 1767, when she was just 13, Phillis wrote a poem about a real-life tale of survival at sea. It was published later that same year in the Newport, Rhode Island Mercury newspaper — her very first published poem. But the poem that gained Phillis international recognition was her elegy to George Whitfield, a prominent evangelical preacher in both Great Britain and New England. That poem was written in 1770, when she was just 17 years old.

Outmaneuvering Prejudice at Home

Despite these early successes, Phillis’ first book-length collection of 28 poems was rejected by the local Boston publishers, who seemed reluctant to support an 18-year old female poet of African descent. So she turned to England and the Countess of Huntingdon.

The Countess had read and admired Phillis’ elegy to George Whitfield, who was her one-time chaplain. The Countess was also a great supporter of both the evangelical and abolitionist causes, so she enlisted London bookseller Archibald Bell to publish Phillis’ collection of poems.

In 1771, Phillis sailed to London to do what amounted to a literary tour ahead of her book’s publication. She was welcomed by a distinguished group of men including a Baron, an Earl, the next Lord Mayor of London and Benjamin Franklin, who happened to be in England at the time.

Emancipation and an Invitation

When her mistress, Susanna Wheatley, became ill, Phillis headed back to Boston. She was still on the boat when her book was finally published in England on September 1, 1773. Soon after her return, in December of 1773, Phillis was emancipated by the Wheatleys.

In 1775, she wrote a poem about George Washington, “To His Excellency, George Washington,” and sent it to him. Washington had just become Commander-in-Chief of the colonial forces during the Revolutionary War, and Phillis’ poem was one of encouragement. Here are the final four lines:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! be thine.

Washington not only wrote back and thanked Phillis for her poem, he invited her to his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. While there is no definitive evidence, many historians believe the two actually met in 1776. Unfortunately, we can only imagine what the soon-to-be first president and the ground-breaking poet might have said to each other.